(30)

- Danish public schools are increasingly struggling with violence and threats against students and teachers, primarily from descendants of MENAPT immigrants. In schools with 30% or more immigrants, violence is twice as prevalent. This is causing a flight to private schools from parents who can afford it (including some Syrians!). Some teachers are quitting the profession as a result, saying "the Quran run the class room".

- Danish women are increasingly feeling unsafe in the nightlife. The mayor of the country's third largest city, Odense, says he knows why: "It's groups of young men with an immigrant background that's causing it. We might as well be honest about that." But unfortunately, the only suggestion he had to deal with the problem was that "when [the women] meet these groups... they should take a big detour around them".

- A soccer club from the infamous ghetto area of Vollsmose got national attention because every other team in their league refused to play them. Due to the team's long history of violent assaults and death threats against opposing teams and referees. Bizarrely leading to the situation were the team got to the top of its division because they'd "win" every forfeited match.

Great AI Steals

David Heinemeier Hansson

Picasso got it right: Great artists steal. Even if he didn’t actually say it, and we all just repeat the quote because Steve

Full

Picasso got it right: Great artists steal. Even if he didn’t actually say it, and we all just repeat the quote because Steve Jobs used it. Because it strikes at the heart of creativity: None of it happens in a vacuum. Everything is inspired by something. The best ideas, angles, techniques, and tones are stolen to build everything that comes after the original.

Furthermore, the way to learn originality is to set it aside while you learn to perfect a copy. You learn to draw by imitating the masters. I learned photography by attempting to recreate great compositions. I learned to program by aping the Ruby standard library.

Stealing good ideas isn’t a detour on the way to becoming a master — it’s the straight route. And it’s nothing to be ashamed of.

This, by the way, doesn’t just apply to art but to the economy as well. Japan became an economic superpower in the 80s by first poorly copying Western electronics in the decades prior. China is now following exactly the same playbook to even greater effect. You start with a cheap copy, then you learn how to make a good copy, and then you don’t need to copy at all.

AI has sped through the phase of cheap copies. It’s now firmly established in the realm of good copies. You’re a fool if you don’t believe originality is a likely next step. In all likelihood, it’s a matter of when, not if. (And we already have plenty of early indications that it’s actually already here, on the edges.)

Now, whether that’s good is a different question. Whether we want AI to become truly creative is a fair question — albeit a theoretical or, at best, moral one. Because it’s going to happen if it can happen, and it almost certainly can (or even has).

Ironically, I think the peanut gallery disparaging recent advances — like the Ghibli fever — over minor details in the copying effort will only accelerate the quest toward true creativity. AI builders, like the Japanese and Chinese economies before them, eager to demonstrate an ability to exceed.

All that is to say that AI is in the "Good Copy" phase of its creative evolution. Expect "The Great Artist" to emerge at any moment.

The Year on Linux

David Heinemeier Hansson

Full

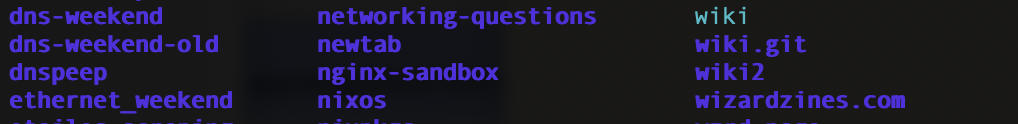

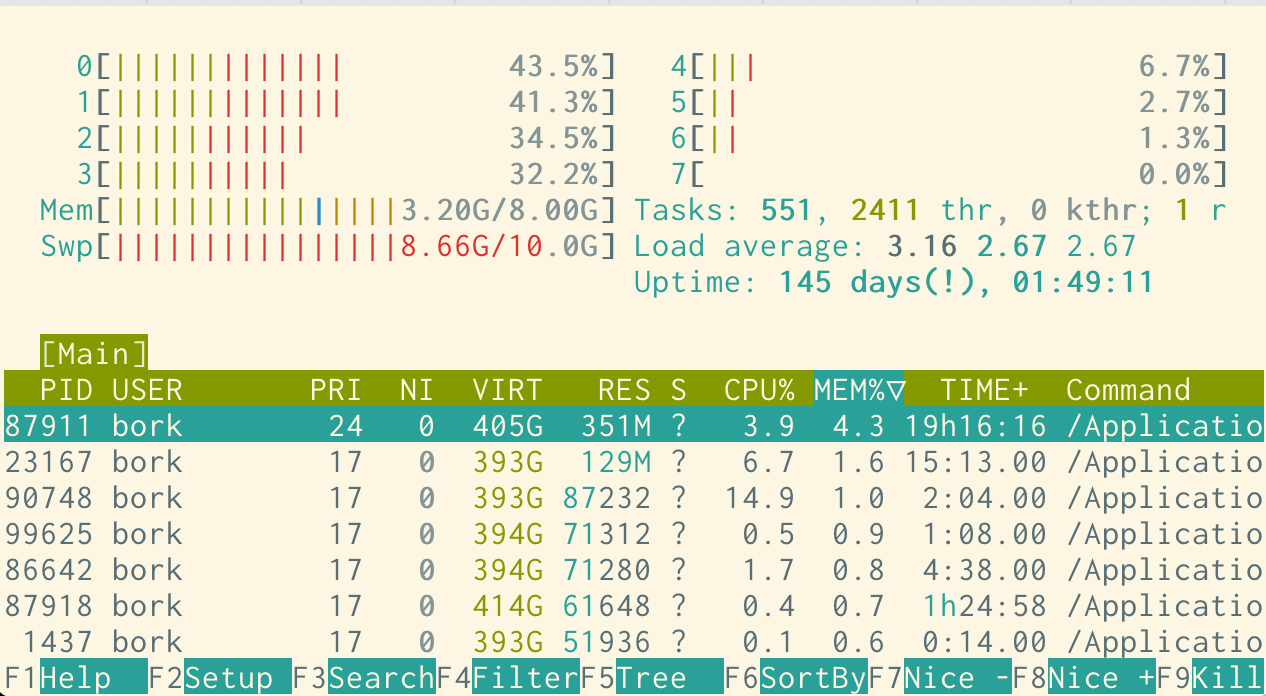

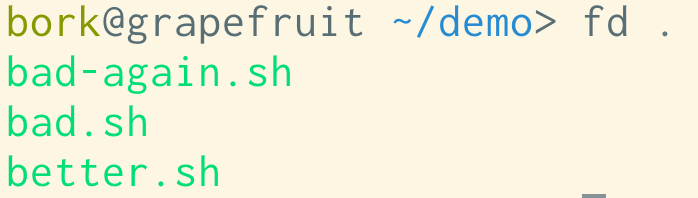

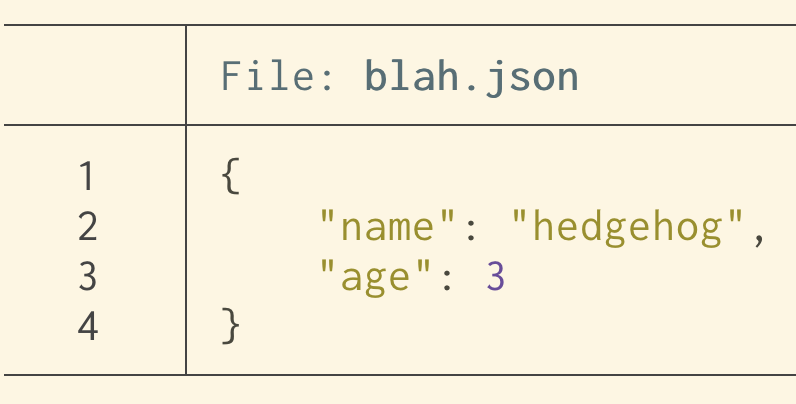

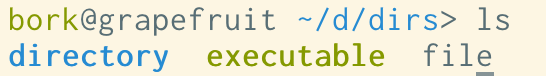

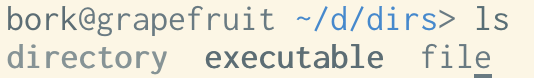

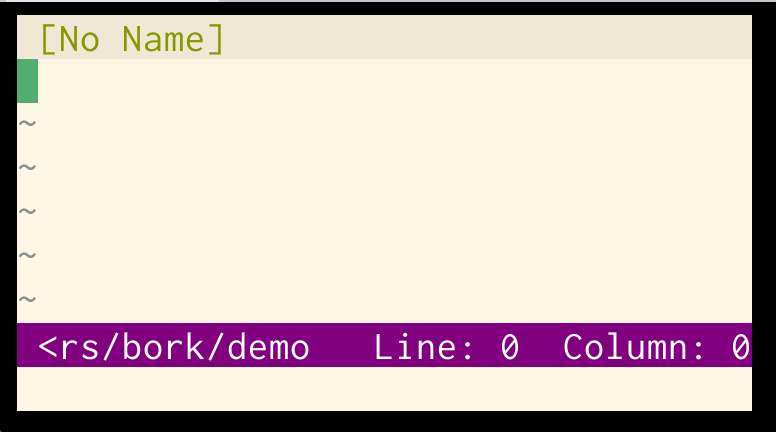

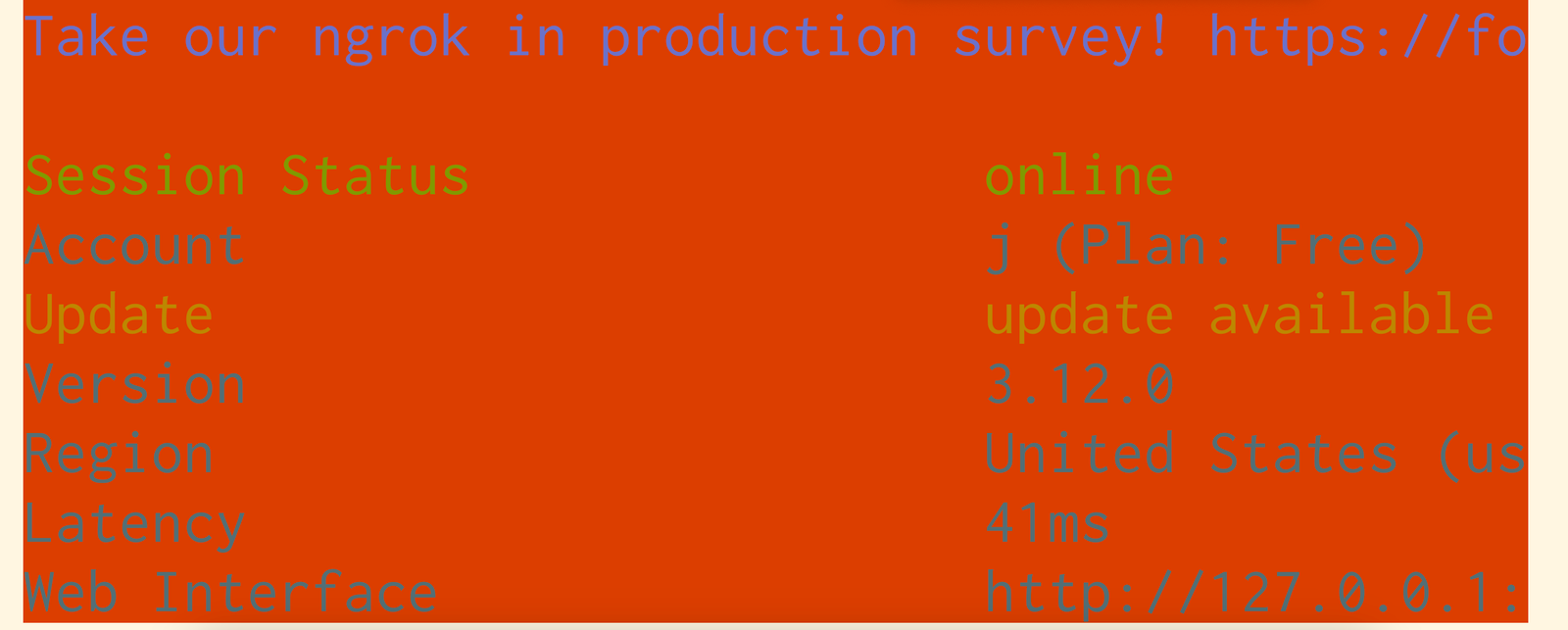

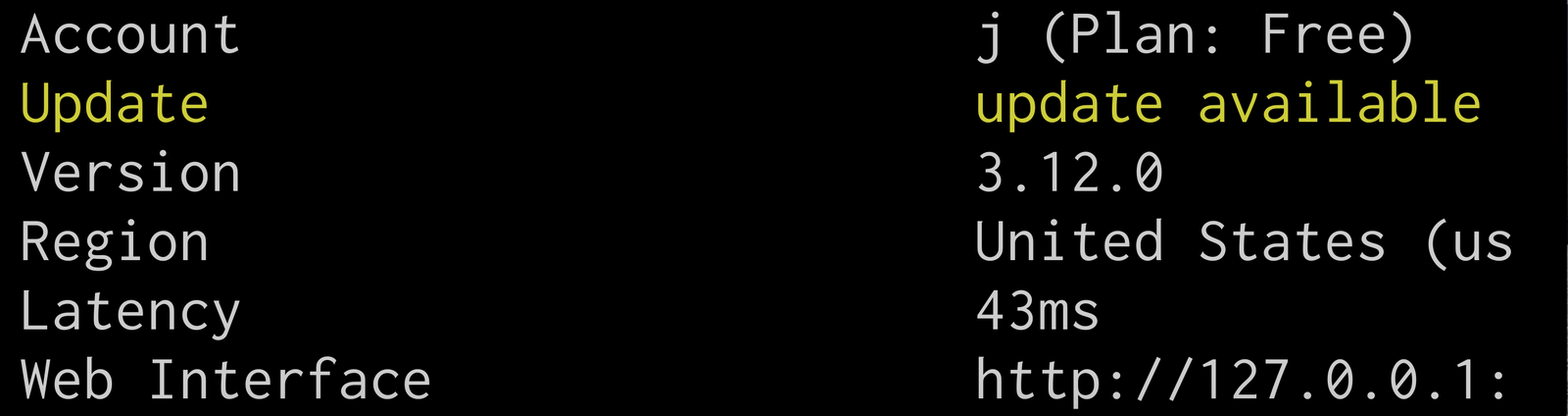

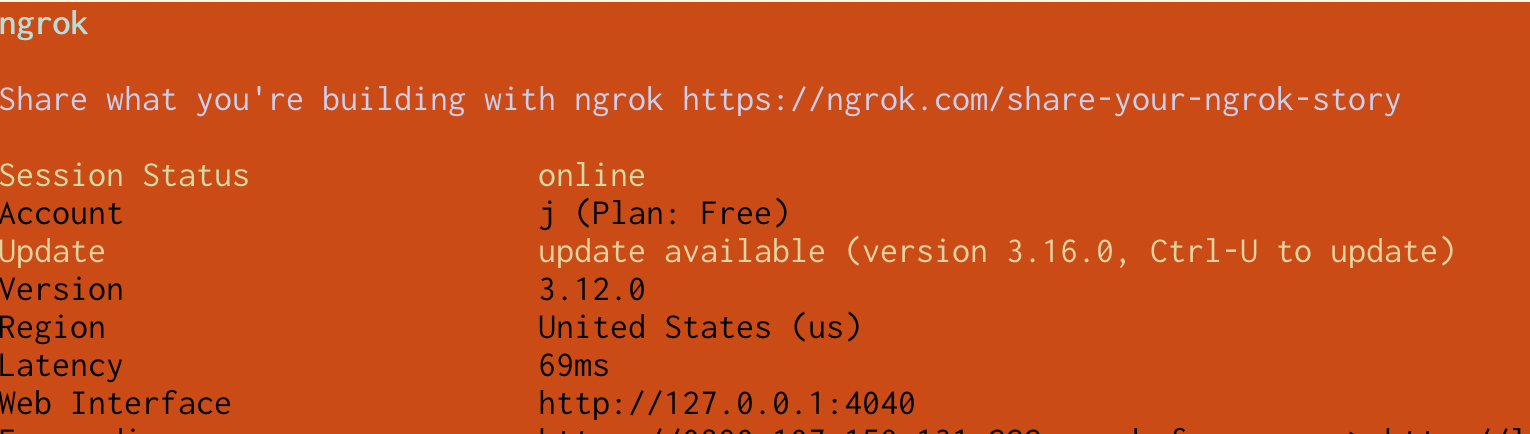

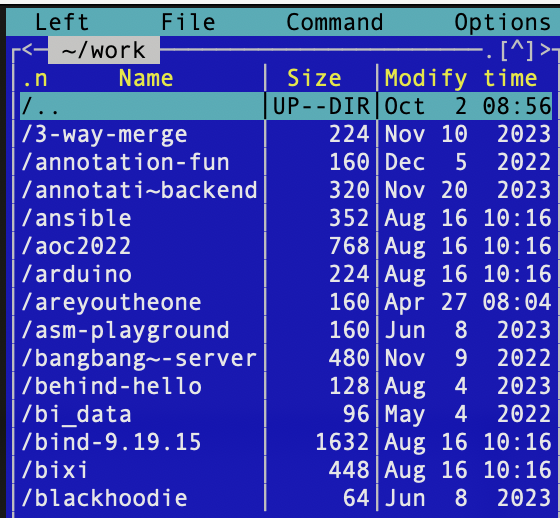

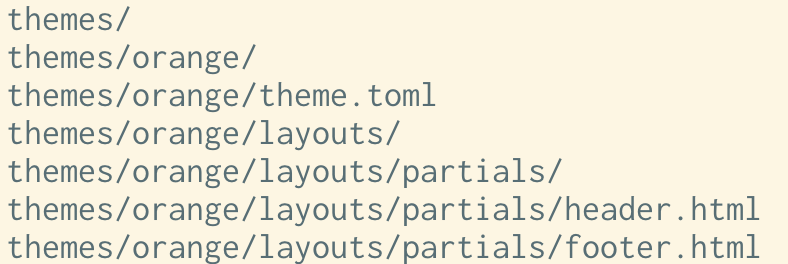

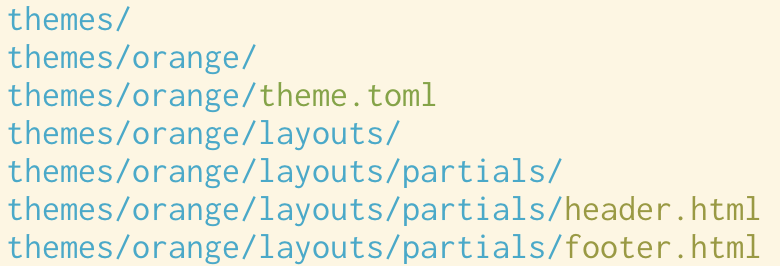

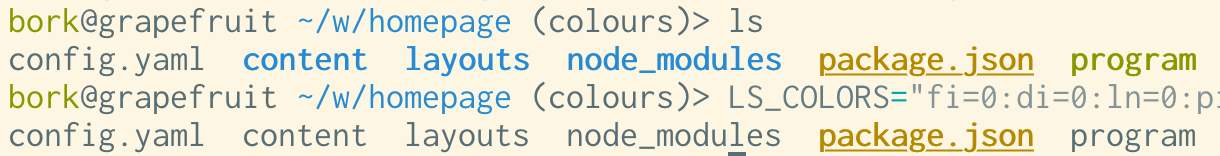

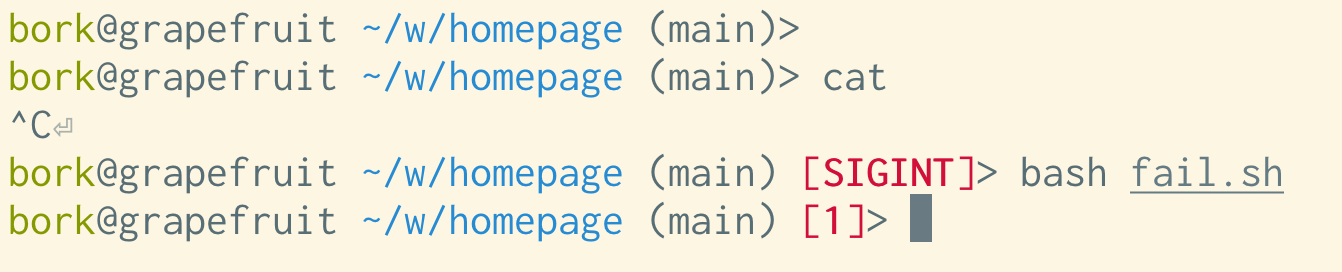

I've been running Linux, Neovim, and Framework for a year now, but it easily feels like a decade or more. That's the funny thing about habits: They can be so hard to break, but once you do, they're also easily forgotten.

That's how it feels having left the Apple realm after two decades inside the walled garden. It was hard for the first couple of weeks, but since then, it’s rarely crossed my mind.

Humans are rigid in the short term, but flexible in the long term. Blessed are the few who can retain the grit to push through that early mental resistance and reach new maxima.

That is something that gets harder with age. I can feel it. It takes more of me now to wipe a mental slate clean and start over. To go back to being a beginner. But the reward for learning something new is as satisfying as ever.

But it's also why I've tried to be modest with the advocacy. I don't know if most developers are better off on Linux. I mean, I believe they are, at some utopian level, especially if they work for the web, using open source tooling. But I don't know if they are as humans with limited will or capacity for change.

Of course, it's fair to say that one doesn't want to. Either because one remain a fan of Apple, in dire need of the remaining edge MacBooks retain on efficiency/battery, or simply content inside the ecosystem. There are plenty of reasons why someone might not want to change. It's not just about rigidity.

Besides, it's a dead end trying to convince anyone of an alternative with the sharp end of a religious argument. That kind of crusading just seeds resentment and stubbornness. I know that all too well.

What I've found to work much better is planting seeds and showing off your plowshare. Let whatever curiosity that blooms find its own way towards your blue sky. The mimetic engine of persuasion runs much cleaner anyway.

And for me, it's primarily about my personal computing workbench regardless of what the world does or doesn't. It was the same with finding Ruby. It's great when others come along for the ride, but I'd also be happy taking the trip solo too.

So consider this a postcard from a year into the Linux, Neovim, and Framework journey. The sun is still shining, the wind is in my hair, and the smile on my lips hasn't been this big since the earliest days of OS X.

Singularity & Serenity

David Heinemeier Hansson

The singularity is the point where artificial intelligence goes parabolic, surpassing humans writ large, and leads to rapid, unpredictable change. The intellectual seed

Full

The singularity is the point where artificial intelligence goes parabolic, surpassing humans writ large, and leads to rapid, unpredictable change. The intellectual seed of this concept was planted back in the '50s by early computer pioneer John von Neumann. So it’s been here since the dawn of the modern computer, but I’ve only just come around to giving the idea consideration as something other than science fiction.

Now, this quickly becomes quasi-religious, with all the terms being as fluid as redemption, absolution, and eternity. What and when exactly is AGI (Artificial General Intelligence) or SAI (Super Artificial Intelligence)? You’ll find a million definitions.

But it really does feel like we’re on the cusp of something. Even the most ardent AI skeptics are probably finding it hard not to be impressed with recent advances. Everything Is Ghibli might seem like a silly gimmick, but to me, it flipped a key bit here: the style persistence, solving text in image generation, and then turning those images into incredible moving pictures.

What makes all this progress so fascinating is that it’s clear nobody knows anything about what the world will look like four years from now. It’s barely been half that time since ChatGPT and Midjourney hit us in 2022, and the leaps since then have been staggering.

I’ve been playing with computers since the Commodore 64 entertained my childhood street with Yie Ar Kung-Fu on its glorious 1 MHz processor. I was there when the web made the internet come alive in the mid-'90s. I lined up for hours for the first iPhone to participate in the grand move to mobile. But I’ve never felt less able to predict what the next token of reality will look like.

When you factor in recent advances in robotics and pair those with the AI brains we’re building, it’s easy to imagine all sorts of futuristic scenarios happening very quickly: from humanoid robots finishing household chores à la The Jetsons (have you seen how good it’s getting at folding?) to every movie we watch being created from a novel prompt on the spot, to, yes, even armies of droids and drones fighting our wars.

This is one of those paradigm shifts with the potential for Total Change. Like the agricultural revolution, the industrial revolution, the information revolution. The kind that rewrites society, where it was impossible to tell in advance where we’d land.

I understand why people find that uncertainty scary. But I choose to receive it as exhilarating instead. What good is it to fret about a future you don’t control anyway? That’s the marvel and the danger of progress: nobody is actually in charge! This is all being driven by a million independent agents chasing irresistible incentives. There’s no pause button, let alone an off-ramp. We’re going to be all-in whether we like it or not.

So we might as well come to terms with that reality. Choose to marvel at the accelerating milestones we've been hitting rather than tremble over the next.

This is something most religions and grand philosophies have long since figured out. The world didn’t just start changing; we’ve had these lurches of forward progress before. And humans have struggled to cope with the transition since the beginning of time. So, the best intellectual frameworks have worked on ways to deal.

Christianity has the Serenity Prayer, which I’ve always been fond of:

God, grant me the serenity

to accept the things I cannot change,

the courage to change the things I can,

and the wisdom to know the difference.

That’s the part most people know. But it actually continues:

Living one day at a time,

enjoying one moment at a time;

accepting hardship as a pathway to peace;

taking, as Jesus did,

this sinful world as it is,

not as I would have it;

trusting that You will make all things right

if I surrender to Your will;

so that I may be reasonably happy in this life

and supremely happy with You forever in the next.

Amen.

What a great frame for the mind!

The Stoics were big on the same concept. Here’s Epictetus:

The Stoics were big on the same concept. Here’s Epictetus:

Some things are in our control and others not. Things in our control are opinion, pursuit, desire, aversion, and, in a word, whatever are our own actions. Things not in our control are body, property, reputation, command, and, in one word, whatever are not our own actions.

Buddhism does this well too. Here’s the Buddha being his wonderfully brief self:

Suffering does not follow one who is free from clinging.

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that all these traditions converged on the idea of letting go of what you can’t control, not clinging to any specific preferred outcome. Because you’re bound to be disappointed that way. You don’t get to know the script to life in advance, but what an incredible show, if you just let it unfold.

This is the broader view of amor fati. You should learn to love not just your own fate, but the fate of the world — its turns, its twists, its progress, and even the inevitable regressions.

The singularity may be here soon, or it may not. You’d be a fool to be convinced either way. But you’ll find serenity in accepting whatever happens.

It's five grand a day to miss our S3 exit

David Heinemeier Hansson

Full

We're spending just shy of $1.5 million/year on AWS S3 at the moment to host files for Basecamp, HEY, and everything else. The only way we were able to get the pricing that low was by signing a four-year contract. That contract expires this summer, June 30, so that's our departure date for the final leg of our cloud exit.

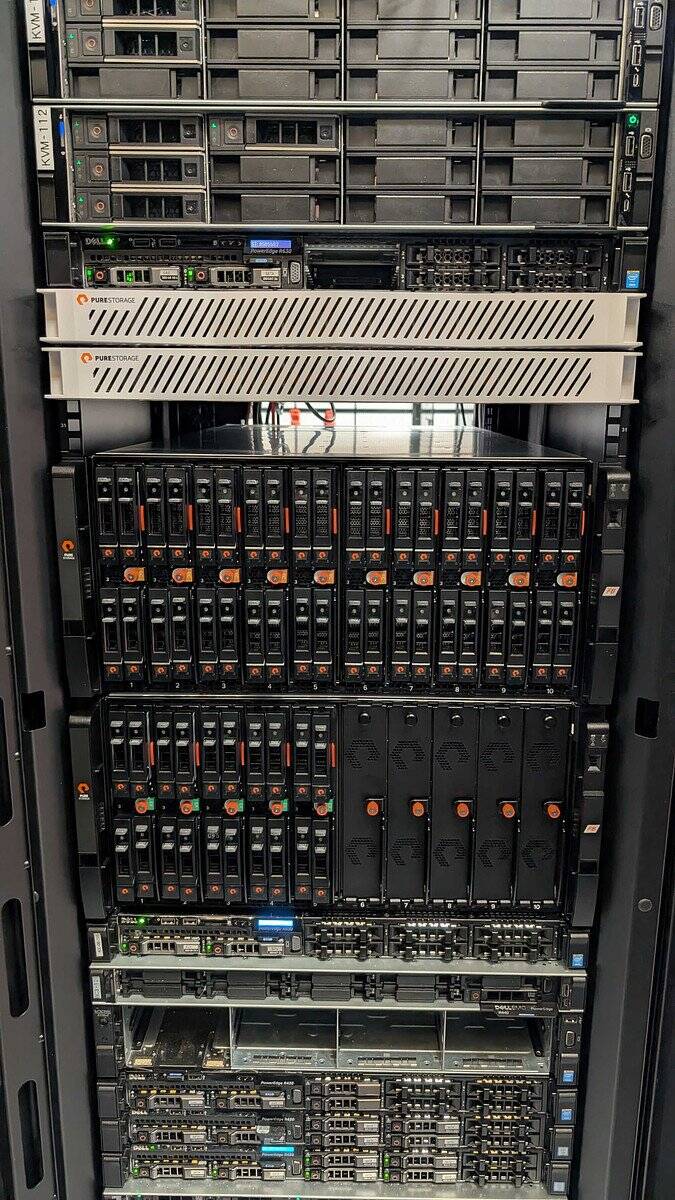

We've already racked the replacement from Pure Storage in our two primary data centers. A combined 18 petabytes, securely replicated a thousand miles apart. It's a gorgeous rack full of blazing-fast NVMe storage modules. Each card in the chassis capable of storing 150TB now.

Pure Storage comes with an S3-compatible API, so no need for CEPH, Minio, or any of the other object storage software solutions you might need, if you were trying to do this exercise on commodity hardware. This makes it pretty easy from the app side to do the swap.

But there's still work to do. We have to transfer almost six petabytes out of S3. In an earlier age, that egress alone would have cost hundreds of thousands of dollars in fees alone. But now AWS offers a free 60-day egress window for anyone who wants to leave, so that drops the cost to $0. Nice!

It takes a while to transfer that much data, though. Even on the fat 40-Gbit pipe we have set aside for the purpose, it'll probably take at least three weeks, once you factor in overhead and some babysitting of the process.

That's when it's good to remind ourselves why June 30th matters. And the reminder math pens out in nice, round numbers for easy recollection: If we don't get this done in time, we'll be paying a cool five thousand dollars a day to continue to use S3 (if all the files are still there). Yikes!

That's $35,000/week! That's $150,000/month!

Pretty serious money for a company of our size. But so are the savings. Over five years, it'll now be almost five million! Maybe even more, depending on the growth in files we need to store for customers. About $1.5 million for the Pure Storage hardware, and a bit less than a million over five years for warranty and support.

But those big numbers always seem a bit abstract to me. The idea of paying $5,000/day, if we miss our departure date, is awfully concrete in comparison.

To hell with forever

David Heinemeier Hansson

Immortality always sounded like a curse to me. But especially now, having passed the halfway point of the average wealthy male life expectancy.

Full

Immortality always sounded like a curse to me. But especially now, having passed the halfway point of the average wealthy male life expectancy. Another scoop of life as big as the one I've already been served seems more than enough, thank you very much.

Does that strike you as morbid?

It's funny, people seem to have no problem understanding satiation when it comes to the individual parts of life. Enough delicious cake, no more rides on the rollercoaster, the end of a great party. But not life itself.

Why?

The eventual end strikes me as beautiful relief. Framing the idea that you can see enough, do enough, be enough. And have enjoyed the bulk of it, without wanting it to go on forever.

Have you seen Highlander? It got panned on its initial release in the 80s. Even Sean Connery couldn't save it with the critics at the time. But I love it. It's one of my all-time favorite movies. It's got a silly story about a worldwide tournament of immortal Highlanders who live forever, lest they get their heads chopped off, and then the last man standing wins... more life?

Yeah, it doesn't actually make a lot of sense. But it nails the sadness of forever. The loneliness, the repetition, the inevitable cynicism with humanity. Who wants to live forever, indeed.

It's the same theme in Björk's wonderfully melancholic song I've Seen It All. It's a great big world, but eventually every unseen element will appear as but a variation on an existing theme. Even surprise itself will succumb to familiarity.

Even before the last day, you can look forward to finality, too. I love racing, but I'm also drawn to the day when the reflexes finally start to fade, and I'll hang up the helmet. One day I will write the last line of Ruby code, too. Sell the last subscription. Write the last tweet. How merciful.

It gets harder with people you love, of course. Harder to imagine the last day with them. But I didn't know my great-great-grandfather, and can easily picture him passing with the satisfaction of seeing his lineage carry on without him.

One way to think of this is to hold life with a loose grip. Like a pair of drumsticks. I don't play, but I'm told that the music flows better when you avoid strangling them in a death grip. And then you enjoy keeping the beat until the song ends.

Amor fati. Amor mori.

Does that strike you as morbid?

It's funny, people seem to have no problem understanding satiation when it comes to the individual parts of life. Enough delicious cake, no more rides on the rollercoaster, the end of a great party. But not life itself.

Why?

The eventual end strikes me as beautiful relief. Framing the idea that you can see enough, do enough, be enough. And have enjoyed the bulk of it, without wanting it to go on forever.

Have you seen Highlander? It got panned on its initial release in the 80s. Even Sean Connery couldn't save it with the critics at the time. But I love it. It's one of my all-time favorite movies. It's got a silly story about a worldwide tournament of immortal Highlanders who live forever, lest they get their heads chopped off, and then the last man standing wins... more life?

Yeah, it doesn't actually make a lot of sense. But it nails the sadness of forever. The loneliness, the repetition, the inevitable cynicism with humanity. Who wants to live forever, indeed.

It's the same theme in Björk's wonderfully melancholic song I've Seen It All. It's a great big world, but eventually every unseen element will appear as but a variation on an existing theme. Even surprise itself will succumb to familiarity.

Even before the last day, you can look forward to finality, too. I love racing, but I'm also drawn to the day when the reflexes finally start to fade, and I'll hang up the helmet. One day I will write the last line of Ruby code, too. Sell the last subscription. Write the last tweet. How merciful.

It gets harder with people you love, of course. Harder to imagine the last day with them. But I didn't know my great-great-grandfather, and can easily picture him passing with the satisfaction of seeing his lineage carry on without him.

One way to think of this is to hold life with a loose grip. Like a pair of drumsticks. I don't play, but I'm told that the music flows better when you avoid strangling them in a death grip. And then you enjoy keeping the beat until the song ends.

Amor fati. Amor mori.

Age is a problem at Apple

David Heinemeier Hansson

The average age of Apple's board members is 68! Nearly half are over 70, and the youngest is 63. It’s not much

Full

The average age of Apple's board members is 68! Nearly half are over 70, and the youngest is 63. It’s not much better with the executive team, where the average age hovers around 60. I’m all for the wisdom of our elders, but it’s ridiculous that the world’s premier tech company is now run by a gerontocracy.

And I think it’s starting to show. The AI debacle is just the latest example. I can picture the board presentation on Genmoji: “It’s what the kids want these days!!”. It’s a dumb feature because nobody on Apple’s board or in its leadership has probably ever used it outside a quick demo.

I’m not saying older people can’t be an asset. Hell, at 45, I’m no spring chicken myself in technology circles! But you need a mix. You need to blend fluid and crystallized intelligence. You need some people with a finger on the pulse, not just some bravely keeping one.

Once you see this, it’s hard not to view slogans like “AI for the rest of us” through that lens. It’s as if AI is like programming a VCR, and you need the grandkids to come over and set it up for you.

By comparison, the average age on Meta’s board is 55. They have three members in their 40s. Steve Jobs was 42 when he returned to Apple in 1997. He was 51 when he introduced the iPhone. And he was gone — from Apple and the world — at 56.

Apple literally needs some fresh blood to turn the ship around.

The 80s are still alive in Denmark

David Heinemeier Hansson

I grew up in the 80s in Copenhagen and roamed the city on my own from an early age. My parents rarely had

Full

I grew up in the 80s in Copenhagen and roamed the city on my own from an early age. My parents rarely had any idea where I went after school, as long as I was home by dinner. They certainly didn’t have direct relationships with the parents of my friends. We just figured things out ourselves. It was glorious.

That’s not the type of childhood we were able to offer our kids in modern-day California. Having to drive everywhere is, of course, its own limitation, but that’s only half the problem. The other half is the expectation that parents are involved in almost every interaction. Play dates are commonly arranged via parents, even for fourth or fifth graders.

The new hysteria over smartphones doesn’t help either, as it cuts many kids off from being able to make their own arrangements entirely (since the house phone has long since died too).

That’s not how my wife grew up in the 80s in America either. The United States of that age was a lot like what I experienced in Denmark: kids roaming around on their own, parents blissfully unaware of where their offspring were much of the time, and absolutely no expectation that parents would arrange play dates or even sleepovers.

I’m sure there are still places in America where life continues like that, but I don’t personally know of any parents who are able to offer that 80s lifestyle to their kids — not in New York, not in Chicago, not in California. Maybe this life still exists in Montana? Maybe it’s a socioeconomic thing? I don’t know.

But what I do know is that Copenhagen is still living in the 80s! We’ve been here off and on over the last several years, and just today, I was struck by the fact that one of our kids had left school after it ended early, biked halfway across town with his friend, and was going to spend the day at his place. And we didn’t get an update on that until much later.

Copenhagen is a compelling city in many ways, but if I were to credit why the US News and World Report just crowned Denmark the best country for raising children in 2025, I’d say it’s the independence — carefree independence. Danish kids roam their cities on their own, manage their social relationships independently, and do so in relative peace and safety.

I’m a big fan of Jonathan Haidt’s work on What Happened In 2013, which he captured in The Coddling of the American Mind. That was a very balanced book, and it called out the lack of unsupervised free play and independence as key contributors to the rise in child fragility.

But it also pinned smartphones and social media with a large share of the blame, despite the fact that the effect, especially on boys, is very much a source of ongoing debate. I’m not arguing that excessive smartphone usage — and certainly social-media brain rot — is good for kids, but I find this explanation is proving to be a bit too easy of a scapegoat for all the ills plaguing American youth.

And it certainly seems like upper-middle-class American parents have decided that blaming the smartphone for everything is easier than interrogating the lack of unsupervised free play, rough-and-tumble interactions for boys, and early childhood independence.

It also just doesn’t track in countries like Denmark, where the smartphone is just as prevalent, if not more so, than in America. My oldest had his own phone by third grade, and so did everyone else in his class — much earlier than Haidt recommends. And it was a key tool for them to coordinate the independence that The Coddling of the American Mind called for more of.

Look, I’m happy to see phones parked during school hours. Several schools here in Copenhagen do that, and there’s a new proposal pending legislation in parliament to make that law across the land. Fine!

But I think it’s delusional of American parents to think that banning the smartphone — further isolating their children from independently managing their social lives — is going to be the one quick fix that cures the anxious generation.

What we need is more 80s-style freedom and independence for kids in America.

Apple needs a new asshole in charge

David Heinemeier Hansson

When things are going well, managers can fool themselves into thinking that people trying their best is all that matters. Poor outcomes are

Full

When things are going well, managers can fool themselves into thinking that people trying their best is all that matters. Poor outcomes are just another opportunity for learning! But that delusion stops working when the wheels finally start coming off — like they have now for Apple and its AI unit. Then you need someone who cares about the outcome above the effort. Then you need an asshole.

In management parlance, an asshole is someone who cares less about feelings or effort and more about outcomes. Steve Jobs was one such asshole. So seems to be Musk. Gates certainly was as well. Most top technology chiefs who've had to really fight in competitive markets for the top prize fall into this category.

Apple's AI management is missing an asshole:

Walker defended his Siri group, telling them that they should be proud. Employees poured their “hearts and souls into this thing,” he said. “I saw so many people giving everything they had in order to make this happen and to make incredible progress together.”

So it's stuck nurturing feelings:

“You might have co-workers or friends or family asking you what happened, and it doesn’t feel good,” Walker said. “It’s very reasonable to feel all these things.” He said others are feeling burnout and that his team will be entitled to time away to recharge to get ready for “plenty of hard work ahead.”

These are both quotes from the Bloomberg report on the disarray inside Apple, following the admission that the star feature of the iPhone 16 — the Apple Intelligence that could reach inside your personal data — won't ship until the iPhone 17, if at all.

John Gruber from Daring Fireball dug up this anecdote from the last time Apple seriously botched a major software launch:

Steve Jobs doesn’t tolerate duds. Shortly after the launch event, he summoned the MobileMe team, gathering them in the Town Hall auditorium in Building 4 of Apple’s campus, the venue the company uses for intimate product unveilings for journalists. According to a participant in the meeting, Jobs walked in, clad in his trademark black mock turtleneck and blue jeans, clasped his hands together, and asked a simple question: “Can anyone tell me what MobileMe is supposed to do?”

Having received a satisfactory answer, he continued, “So why the fuck doesn’t it do that?”

For the next half-hour Jobs berated the group. “You’ve tarnished Apple’s reputation,” he told them. “You should hate each other for having let each other down.” The public humiliation particularly infuriated Jobs.

Can you see the difference? This is an asshole in action.

Apple needs to find a new asshole and put them in charge of the entire product line. Cook clearly isn't up to the task, and the job is currently spread thinly across a whole roster of senior VPs. Little fiefdoms. This is poison to the integrated magic that was Apple's trademark for so long.

The most interesting people

David Heinemeier Hansson

We didn’t used to need an explanation for having kids. That was just life. That’s just what you did. But now we do,

Full

We didn’t used to need an explanation for having kids. That was just life. That’s just what you did. But now we do, because now we don’t.

So allow me: Having kids means making the most interesting people in the world. Not because toddlers or even teenagers are intellectual oracles — although life through their eyes is often surprising and occasionally even profound — but because your children will become the most interesting people to you.

That’s the important part. To you.

There are no humans on earth I’m as interested in as my children. Their maturation and growth are the greatest show on the planet. And having a front-seat ticket to this performance is literally the privilege of a lifetime.

But giving a review of this incredible show just doesn’t work. I could never convince a stranger that my children are the most interesting people in the world, because they wouldn’t be, to them.

So words don’t work. It’s a leap of faith. All I can really say is this: Trust me, bro.

We wash our trash to repent for killing God

David Heinemeier Hansson

Denmark is technically and officially still a Christian nation. Lutheranism is written into the constitution. The government has a ministry for the

Full

Denmark is technically and officially still a Christian nation. Lutheranism is written into the constitution. The government has a ministry for the church. Most Danes pay 1% of their earnings directly to fund the State religion. But God is as dead here as anywhere in the Western world. Less than 2% attend church service on a weekly basis. So one way to fill the void is through climate panic and piety.

I mean, these days, you can scarcely stroll past stores in the swankier parts of Copenhagen without being met by an endless parade of ads carrying incantations towards sustainability, conservation, and recycling. It's everywhere.

Hilariously, sometimes this even includes recommending that customers don’t buy the product. I went to a pita place for lunch the other day. The menu had a meat shawarma option, and alongside it was a plea not to order it too often because it’d be better for the planet if you picked the falafel instead.

But the hysteria peaks with the trash situation. It’s now common for garbage rooms across Copenhagen to feature seven or more bins for sorting disposals. Despite trash-sorting robots being able to do this job far better than humans in most cases, you see Danes dutifully sorting and subdividing their waste with a pious obligation worthy of the new climate deity.

Yet it’s not even the sorting that gets me — it’s the washing. You can’t put plastic containers with food residue into the recycling bucket, so you have to rinse them first. This leads to the grotesque daily ritual of washing trash (and wasting water galore in the process!).

Plus, most people in Copenhagen live in small apartments, and all that separated trash has to be stored separately until the daily pilgrimage to the trash room. So it piles up all over the place.

This is exactly what Nietzsche meant by “God is dead” — his warning that we’d need to fill the void with another centering orientation toward the world. And clearly, climatism is stepping up as a suitable alternative for the Danes. It’s got guilt, repentance, and plenty of rituals to spare. Oh, and its heretics too.

Look, I'd like a clean planet as much as the next sentient being. I'm not crying any tears over the fact that gas-powered cars are quickly disappearing from the inner-city of Copenhagen. I love biking! I wish we'd get a move on with nuclear for consistent, green energy. But washing or sorting my trash when a robot could do a better job just to feel like "I'm doing my part"? No.

It’s like those damn paper straws that crumble halfway through your smoothie. The point of it all seems to be self-inflicted, symbolic suffering — solely to remind you of your good standing with the sacred lord of recycling, refuting the plastic devil.

And worse, these small, meaningless acts of pious climate service end up working as catholic indulgences. We buy a good conscience washing trash so we don't have to feel guilty setting new records flying for fun.

I’m not religious, but I’m starting to think it’d be nicer to spend a Sunday morning in the presence of the Almighty than to keep washing trash as pagan replacement therapy.

Our switch to Kamal is complete

David Heinemeier Hansson

In a fit of frustration, I wrote the first version of Kamal in six weeks at the start of 2023.

Full

In a fit of frustration, I wrote the first version of Kamal in six weeks at the start of 2023. Our plan to get out of the cloud was getting bogged down in enterprisey pricing and Kubernetes complexity. And I refused to accept that running our own hardware had to be that expensive or that convoluted. So I got busy building a cheap and simple alternative.

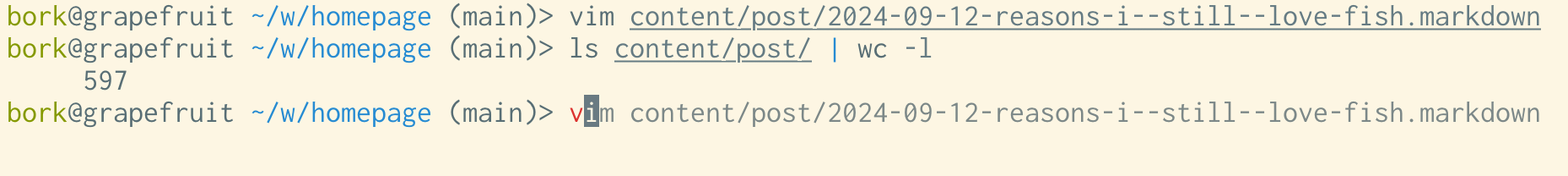

Now, just two years later, Kamal is deploying every single application in our entire heritage fleet, and everything in active development. Finalizing a perfectly uniform mode of deployment for every web app we've built over the past two decades and still maintain.

See, we have this obsession at 37signals: That the modern build-boost-discard cycle of internet applications is a scourge. That users ought to be able to trust that when they adopt a system like Basecamp or HEY, they don't have to fear eviction from the next executive re-org. We call this obsession Until The End Of The Internet.

That obsession isn't free, but it's worth it. It means we're still operating the very first version of Basecamp for thousands of paying customers. That's the OG code base from 2003! Which hasn't seen any updates since 2010, beyond security patches, bug fixes, and performance improvements. But we're still operating it, and, along with every other app in our heritage collection, deploying it with Kamal.

That just makes me smile, knowing that we have customers who adopted Basecamp in 2004, and are still able to use the same system some twenty years later. In the meantime, we've relaunched and dramatically improved Basecamp many times since. But for customers happy with what they have, there's no forced migration to the latest version.

I very much had all of this in mind when designing Kamal. That's one of the reasons I really love Docker. It allows you to encapsulate an entire system, with all of its dependencies, and run it until the end of time. Kind of how modern gaming emulators can run the original ROM of Pac-Man or Pong to perfection and eternity.

Kamal seeks to be but a simple wrapper and workflow around this wondrous simplicity. Complexity is but a bridge — and a fragile one at that. To build something durable, you have to make it simple.

Closing the borders alone won't fix the problems

David Heinemeier Hansson

Denmark has been reaping lots of delayed accolades from its relatively strict immigration policy lately. The Swedes and the

Full

Denmark has been reaping lots of delayed accolades from its relatively strict immigration policy lately. The Swedes and the Germans in particular are now eager to take inspiration from The Danish Model, given their predicaments. The very same countries that until recently condemned the lack of open-arms/open-border policies they would champion as Moral Superpowers.

But even in Denmark, thirty years after the public opposition to mass immigration started getting real political representation, the consequences of culturally-incompatible descendants from MENAPT continue to stress the high-trust societal model.

Here are just three major cases that's been covered in the Danish media in 2025 alone:

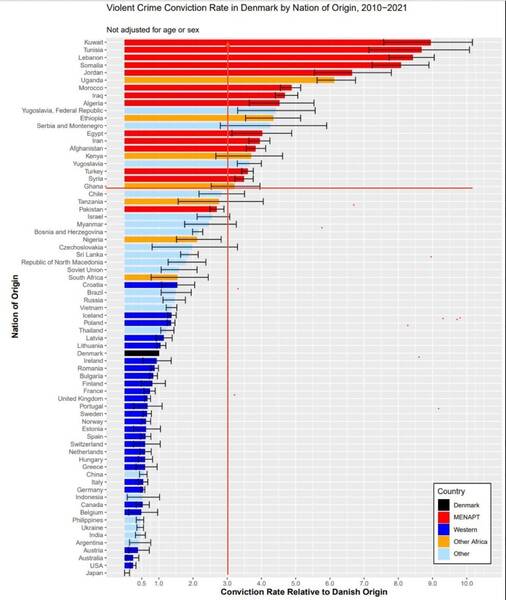

Problems of this sort have existed in Denmark for well over thirty years. So in a way, none of this should be surprising. But it actually is. Because it shows that long-term assimilation just isn't happening at a scale to tackle these problems. In fact, data shows the opposite: Descendants of MENAPT immigrants are more likely to be violent and troublesome than their parents.

That's an explosive point because it blows up the thesis that time will solve these problems. Showing instead that it actually just makes it worse. And then what?

This is particularly pertinent in the analysis of Sweden. After the "far right" party of the Swedish Democrats got into government, the new immigrant arrivals have plummeted. But unfortunately, the net share of immigrants is still increasing, in part because of family reunifications, and thus the problems continue.

Meaning even if European countries "close the borders", they're still condemned to deal with the damning effects of maladjusted MENAPT immigrant descendants for decades to come. If the intervention stops there.

There are no easy answers here. Obviously, if you're in a hole, you should stop digging. And Sweden has done just that. But just because you aren't compounding the problem doesn't mean you've found a way out. Denmark proves to be both a positive example of minimizing the digging while also a cautionary tale that the hole is still there.

Apple does AI as Microsoft did mobile

David Heinemeier Hansson

When the iPhone first appeared in 2007, Microsoft was sitting pretty with their mobile strategy. They'd been early to the market with Windows

Full

When the iPhone first appeared in 2007, Microsoft was sitting pretty with their mobile strategy. They'd been early to the market with Windows CE, they were fast-following the iPod with their Zune. They also had the dominant operating system, the dominant office package, and control of the enterprise. The future on mobile must have looked so bright!

But of course now, we know it wasn't. Steve Ballmer infamously dismissed the iPhone with a chuckle, as he believed all of Microsoft's past glory would guarantee them mobile victory. He wasn't worried at all. He clearly should have been!

After reliving that Ballmer moment, it's uncanny to watch this CNBC interview from one year ago with Johny Srouji and John Ternus from Apple on their AI strategy. Ternus even repeats the chuckle!! Exuding the same delusional confidence that lost Ballmer's Microsoft any serious part in the mobile game.

But somehow, Apple's problems with AI seem even more dire. Because there's apparently no one steering the ship. Apple has been promising customers a bag of vaporware since last fall, and they're nowhere close to being able to deliver on the shiny concept demos. The ones that were going to make Apple Intelligence worthy of its name, and not just terrible image generation that is years behind the state of the art.

Nobody at Apple seems able or courageous enough to face the music: Apple Intelligence sucks. Siri sucks. None of the vaporware is anywhere close to happening. Yet as late as last week, you have Cook promoting the new MacBook Air with "Apple Intelligence". Yikes.

This is partly down to the org chart. John Giannandrea is Apple's VP of ML/AI, and he reports directly to Tim Cook. He's been in the seat since 2018. But Cook evidently does not have the product savvy to be able to tell bullshit from benefit, so he keeps giving Giannandrea more rope. Now the fella has hung Apple's reputation on vaporware, promised all iPhone 16 customers something magical that just won't happen, and even spec-bumped all their devices with more RAM for nothing but diminished margins. Ouch.

This is what regression to the mean looks like. This is what fiefdom management looks like. This is what having a company run by a logistics guy looks like. Apple needs a leadership reboot, stat. That asterisk is a stain.

Beans and vibes in even measure

David Heinemeier Hansson

Bean counters have a bad rep for a reason. And it’s not because paying attention to the numbers is inherently unreasonable. It’s because

Full

Bean counters have a bad rep for a reason. And it’s not because paying attention to the numbers is inherently unreasonable. It’s because weighing everything exclusively by its quantifiable properties is an impoverished way to view business (and the world!).

Nobody presents this caricature better than the MBA types who think you can manage a business entirely in the abstract realm of "products," "markets," "resources," and "deliverables." To hell with that. The death of all that makes for a breakout product or service happens when the generic lingo of management theory takes over.

This is why founder-led operations often keep an edge. Because when there’s someone at the top who actually gives a damn about cars, watches, bags, software, or whatever the hell the company makes, it shows up in a million value judgments that can’t be quantified neatly on a spreadsheet.

Now, I love a beautiful spreadsheet that shows expanding margins, healthy profits, and customer growth as much as any business owner. But much of the time, those figures are derivatives of doing all the stuff that you can’t compute and that won’t quantify.

But this isn’t just about running a better business by betting on unquantifiable elements that you can’t prove but still believe matter. It’s also about the fact that doing so is simply more fun! It’s more congruent. It’s vibe management.

And no business owner should ever apologize for having fun, following their instincts, or trusting that the numbers will eventually show that doing the right thing, the beautiful thing, the poetic thing is going to pay off somehow. In this life or the next.

Of course, you’ve got to get the basics right. Make more than you spend. Don’t get out over your skis. But once there’s a bit of margin, you owe it to yourself to lean on that cushion and lead the business primarily on the basis of good vibes and a long vision.

Air purifiers are a simple answer to allergies

David Heinemeier Hansson

I developed seasonal allergies relatively late in life. From my late twenties onward, I spent many miserable days in the throes of sneezing,

Full

I developed seasonal allergies relatively late in life. From my late twenties onward, I spent many miserable days in the throes of sneezing, headache, and runny eyes. I tried everything the doctors recommended for relief. About a million different types of medicine, several bouts of allergy vaccinations, and endless testing. But never once did an allergy doctor ask the basic question: What kind of air are you breathing?

Turns out that's everything when you're allergic to pollen, grass, and dust mites! The air. That's what's carrying all this particulate matter, so if your idea of proper ventilation is merely to open a window, you're inviting in your nasal assailants. No wonder my symptoms kept escalating.

For me, the answer was simply to stop breathing air full of everything I'm allergic to while working, sleeping, and generally just being inside. And the way to do that was to clean the air of all those allergens with air purifiers running HEPA-grade filters.

That's it. That was the answer!

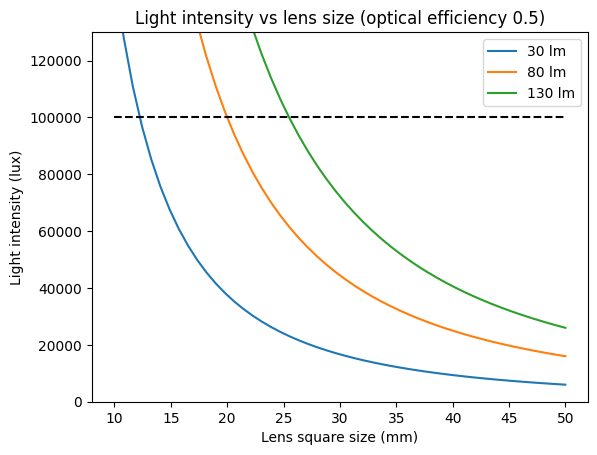

After learning this, I outfitted everywhere we live with these machines of purifying wonder: One in the home office, one in the living area, one in the bedroom. All monitored for efficiency using Awair air sensors. Aiming to have the PM2.5 measure read a fat zero whenever possible.

In America, I've used the Alen BreatheSmart series. They're great. And in Europe, I've used the Philips ones. Also good.

It's been over a decade like this now. It's exceptionally rare that I have one of those bad allergy days now. It can still happen, of course — if I spend an entire day outside, breathing in allergens in vast quantities. But as with almost everything, the dose makes the poison. The difference between breathing in some allergens, some of the time, is entirely different from breathing all of it, all of the time.

I think about this often when I see a doctor for something. Here was this entire profession of allergy specialists, and I saw at least a handful of them while I was trying to find a medical solution. None of them even thought about dealing with the environment. The cause of the allergy. Their entire field of view was restricted to dealing with mitigation rather than prevention.

Not every problem, medical or otherwise, has a simple solution. But many problems do, and you have to be careful not to be so smart that you can't see it.

Human service is luxury

David Heinemeier Hansson

Maybe one day AI will answer every customer question flawlessly, but we're nowhere near that reality right now. I can't tell you how

Full

Maybe one day AI will answer every customer question flawlessly, but we're nowhere near that reality right now. I can't tell you how often I've been stuck in some god-forsaken AI loop or phone tree WHEN ALL I WANT IS A HUMAN. So I end up either just yelling "operator", "operator", "operator" (the modern-day mayday!) or smashing zero over and over. It's a unworthy interaction for any premium service.

Don't get me wrong. I'm pretty excited about AI. I've seen it do some incredible things. And of course it's just going to keep getting better. But in our excitement about the technical promise, I think we're forgetting that humans need more than correct answers. Customer service at its best also offers understanding and reassurance. It offers a human connection.

Especially as AI eats the low-end, commodity-style customer support. The sort that was always done poorly, by disinterested people, rapidly churning through a perceived dead-end job, inside companies that only ever saw support as a cost center. Yeah, nobody is going to cry a tear for losing that.

But you know that isn't all there is to customer service. Hopefully you've had a chance to experience what it feels like when a cheerful, engaged human is interested in helping you figure out what's wrong or how to do something right. Because they know exactly what they're talking about. Because they've helped thousands of others through exactly the same situation. That stuff is gold.

Partly because it feels bespoke. A customer service agent who's good at their job knows how to tailor the interaction not just to your problem, but to your temperament. Because they've seen all the shapes. They can spot an angry-but-actually-just-frustrated fit a thousand miles away. They can tell a timid-but-curious type too. And then deliver exactly what either needs in that moment. That's luxury.

That's our thesis for Basecamp, anyway. That by treating customer service as a career, we'll end up with the kind of agents that embody this luxury, and our customers will feel the difference.

AMD in everything

David Heinemeier Hansson

Back in the mid 90s, I had a friend who was really into raytracing, but needed to nurture his hobby on a budget.

Full

Back in the mid 90s, I had a friend who was really into raytracing, but needed to nurture his hobby on a budget. So instead of getting a top-of-the-line Intel Pentium machine, he bought two AMD K5 boxes, and got a faster rendering flow for less money. All I cared about in the 90s was gaming, though, and for that, Intel was king, so to me, AMD wasn't even a consideration.

And that's how it stayed for the better part of the next three decades. AMD would put out budget parts that might make economic sense in narrow niches, but Intel kept taking all the big trophies in gaming, in productivity, and on the server.

As late as the end of the 2010s, we were still buying Intel for our servers at 37signals. Even though AMD was getting more competitive, and the price-watt-performance equation was beginning to tilt in their favor.

By the early 2020s, though, AMD had caught up on the server, and we haven't bought Intel since. The AMD EPYC line of chips are simply superior to anything Intel offers in our price/performance window. Today, the bulk of our new fleet run on dual EPYC 9454s for a total of 96 cores(!) per machine. They're awesome.

It's been the same story on the desktop and laptop for me. After switching to Linux last year, I've been all in on AMD. My beloved Framework 13 is rocking an AMD 7640U, and my desktop machine runs on an AMD 7950X. Oh, and my oldest son just got a new gaming PC with an AMD 9900X, and my middle son has a AMD 8945HS in his gaming laptop. It's all AMD in everything!

So why is this? Well, clearly the clever crew at AMD is putting out some great CPU designs lately with Lisa Su in charge. I'm particularly jazzed about the upcoming Framework desktop, which runs the latest Max 395+ chip, and can apportion up to 110GB of memory as VRAM (great for local AI!). This beast punches a multi-core score that's on par with that of an M4 Pro, and it's no longer that far behind in single-core either. But all the glory doesn't just go to AMD, it's just as much a triumph of TSMC.

TSMC stands for Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company. They're the world leader in advanced chip making, and key to the story of how Apple was able to leapfrog the industry with the M-series chips back in 2020. Apple has long been the top customer for TSMC, so they've been able to reserve capacity on the latest manufacturing processes (called "nodes"), and as a result had a solid lead over everyone else for a while.

But that lead is evaporating fast. That new Max+ 395 is showing that AMD has nearly caught up in terms of raw grunt, and the efficiency is no longer a million miles away either. This is again largely because AMD has been able to benefit from the same TSMC-powered progress that's also propelling Apple.

But you know who it's not propelling? Intel. They're still trying to get their own chip-making processes to perform competitively, but so far it looks like they're just falling further and further behind. The latest Intel boards are more expensive and run slower than the competition from Apple, AMD, and Qualcomm. And there appears to be no easy fix to sort it all out around the corner.

TSMC really is lifting all the boats behind its innovation locks. Qualcomm, just like AMD, have nearly caught up to Apple with their latest chips. The 8 Elite unit in my new Samsung S25 is faster than the A18 Pro in the iPhone 16 Pro in multi-core tests, and very close in single-core. It's also just as efficient now.

This is obviously great for Android users, who for a long time had to suffer the indignity of truly atrocious CPU performance compared to the iPhone. It was so bad for a while that we had to program our web apps differently for Android, because they simply didn't have the power to run JavaScript fast enough! But that's all history now.

But as much as I now cheer for Qualcomm's chips, I'm even more chuffed about the fact that AMD is on a roll. I spend far more time in front of my desktop than I do any other computer, and after dumping Apple, it's a delight to see that the M-series advantage is shrinking to irrelevance fast. There's of course still the software reason for why someone would pick Apple, and they continue to make solid hardware, but the CPU playing field is now being leveled.

This is obviously a good thing if you're a fan of Linux, like me. Framework in particular has invigorated a credible alternative to the sleek, unibody but ultimately disposable nature of the reigning MacBook laptops. By focusing on repairability, upgradeability, and superior keyboards, we finally have an alternative for developer laptops that doesn't just feel like a cheap copy of a MacBook. And thanks to AMD pushing the envelope, these machines are rapidly closing the remaining gaps in performance and efficiency.

And oh how satisfying it must be to sit as CEO of AMD now. The company was founded just one year after Intel, back in 1969, but for its entire existence, it's lived in the shadow of its older brother. Now, thanks to TSMC, great leadership from Lisa Su, and a crack team of chip designers, they're finally reaping the rewards. That is one hell of a journey to victory!

So three cheers for AMD! A tip of the hat to TSMC. And what a gift to developers and computer enthusiasts everywhere that Apple once more has some stiff competition in the chip space.

The New York Times gives liberals The Danish Permission to pivot on mass immigration

David Heinemeier Hansson

One of the key roles The New York Times plays in American society is as guardians of the liberal Overton window. Its

Full

One of the key roles The New York Times plays in American society is as guardians of the liberal Overton window. Its editorial line sets the terms for what's permissible to discuss in polite circles on the center left. Whether it's covid mask efficiency, trans kids, or, now, mass immigration. When The New York Times allows the counter argument to liberal orthodoxy to be published, it signals to its readers that it's time to pivot.

On mass immigration, the center-left liberal orthodoxy has for the last decade in particular been that this is an unreserved good. It's cultural enrichment! It's much-needed workers! It's a humanitarian imperative! Any opposition was treated as de-facto racism, and the idea that a country would enforce its own borders as evidence of early fascism. But that era is coming to a close, and The New York Times is using The Danish Permission to prepare its readers for the end.

As I've often argued, Denmark is an incredibly effective case study in such arguments, because it's commonly thought of as the holy land of progressivism. Free college, free health care, amazing public transit, obsessive about bikes, and a solid social safety net. It's basically everything people on the center left ever thought they wanted from government. In theory, at least.

In practice, all these government-funded benefits come with a host of trade-offs that many upper middle-class Americans (the primary demographic for The New York Times) would find difficult to swallow. But I've covered that in detail in The reality of the Danish fairytale, so I won't repeat that here.

Instead, let's focus on the fact that The New York Times is now begrudgingly admitting that the main reason Europe has turned to the right, in election after election recently, is due to the problems stemming from mass immigration across the continent and the channel.

For example, here's a bit about immigrant crime being higher:

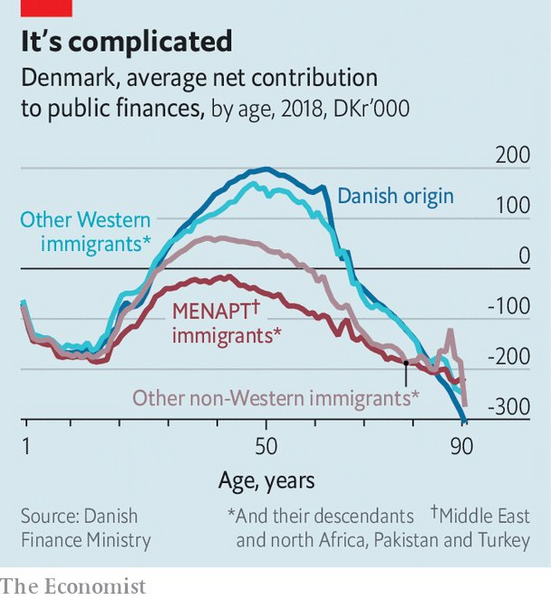

Crime and welfare were also flashpoints: Crime rates were substantially higher among immigrants than among native Danes, and employment rates were much lower, government data showed.

It wasn't long ago that recognizing higher crime rates among MENAPT immigrants to Europe was seen as a racist dog whistle. And every excuse imaginable was leveled at the undeniable statistics showing that immigrants from countries like Tunisia, Lebanon, and Somalia are committing violent crime at rates 7-9 times higher than ethnic Danes (and that these statistics are essentially the same in Norway and Finland too).

Or how about this one: Recognizing that many immigrants from certain regions were loafing on the welfare state in ways that really irked the natives:

One source of frustration was the fact that unemployed immigrants sometimes received resettlement payments that made their welfare benefits larger than those of unemployed Danes.

Or the explicit acceptance that a strong social welfare state requires a homogeneous culture in order to sustain the trust needed for its support:

Academic research has documented that societies with more immigration tend to have lower levels of social trust and less generous government benefits. Many social scientists believe this relationship is one reason that the United States, which accepted large numbers of immigrants long before Europe did, has a weaker safety net. A 2006 headline in the British publication The Economist tartly summarized the conclusion from this research as, “Diversity or the welfare state: Choose one.”

Diversity or welfare! That again would have been an absolutely explosive claim to make not all that long ago.

Finally, there's the acceptance that cultural incompatibility, such as on the role of women in society, is indeed a problem:

Gender dynamics became a flash point: Danes see themselves as pioneers for equality, while many new arrivals came from traditional Muslim societies where women often did not work outside the home and girls could not always decide when and whom to marry.

It took a while, but The New York Times is now recognizing that immigrants from some regions really do commit vastly more violent crime, are net-negative contributors to the state budgets (by drawing benefits at higher rates and being unemployed more often), and that together with the cultural incompatibilities, end up undermining public trust in the shared social safety net.

The consequence of this admission is dawning not only on The New York Times, but also on other liberal entities around Europe:

Tellingly, the response in Sweden and Germany has also shifted... Today many Swedes look enviously at their neighbor. The foreign-born population in Sweden has soared, and the country is struggling to integrate recent arrivals into society. Sweden now has the highest rate of gun homicides in the European Union, with immigrants committing a disproportionate share of gun violence. After an outburst of gang violence in 2023, Ulf Kristersson, the center-right prime minister, gave a televised address in which he blamed “irresponsible immigration policy” and “political naïveté.” Sweden’s center-left party has likewise turned more restrictionist.

All these arguments are in service of the article's primary thesis: To win back power, the left, in Europe and America, must pivot on mass immigration, like the Danes did. Because only by doing so are they able to counter the threat of "the far right".

The piece does a reasonable job accounting for the history of this evolution in Danish politics, except for the fact that it leaves out the main protagonist. The entire account is written from the self-serving perspective of the Danish Social Democrats, and it shows. It tells a tale of how it was actually Social Democrat mayors who first spotted the problems, and well, it just took a while for the top of the party to correct. Bullshit.

The real reason the Danes took this turn is that "the far right" won in Denmark, and The Danish People's Party deserve the lion's share of the credit. They started in 1995, quickly set the agenda on mass immigration, and by 2015, they were the second largest party in the Danish parliament.

Does that story ring familiar? It should. Because it's basically what's been happening in Sweden, France, Germany, and the UK lately. The mainstream parties have ignored the grave concerns about mass immigration from its electorate, and only when "the far right" surged as a result, did the center left and right parties grow interested in changing course.

Now on some level, this is just democracy at work. But it's also hilarious that this process, where voters choose parties that champion the causes they care about, has been labeled The Grave Threat to Democracy in recent years. Whether it's Trump, Le Pen, Weidel, or Kjærsgaard, they've all been met with contempt or worse for channeling legitimate voter concerns about immigration.

I think this is the point that's sinking in at The New York Times. Opposition to mass immigration and multi-culturalism in Europe isn't likely to go away. The mayhem that's swallowing Sweden is a reality too obvious to ignore. And as long as the center left keeps refusing to engage with the topic honestly, and instead hides behind some anti-democratic firewall, they're going to continue to lose terrain.

Again, this is how democracies are supposed to work! If your political class is out of step with the mood of the populace, they're supposed to lose. And this is what's broadly happening now. And I think that's why we're getting this New York Times pivot. Because losing sucks, and if you're on the center left, you'd like to see that end.

Stick with the customer

David Heinemeier Hansson

One of the biggest mistakes that new startup founders make is trying to get away from the customer-facing roles too early. Whether it's

Full

One of the biggest mistakes that new startup founders make is trying to get away from the customer-facing roles too early. Whether it's customer support or it's sales, it's an incredible advantage to have the founders doing that work directly, and for much longer than they find comfortable.

The absolute worst thing you can do is hire a sales person or a customer service agent too early. You'll miss all the golden nuggets that customers throw at you for free when they're rejecting your pitch or complaining about the product. Seeing these reasons paraphrased or summarized destroy all the nutrients in their insights. You want that whole-grain feedback straight from the customers' mouth!

When we launched Basecamp in 2004, Jason was doing all the customer service himself. And he kept doing it like that for three years!! By the time we hired our first customer service agent, Jason was doing 150 emails/day. The business was doing millions of dollars in ARR. And Basecamp got infinitely, better both as a market proposition and as a product, because Jason could funnel all that feedback into decisions and positioning.

For a long time after that, we did "Everyone on Support". Frequently rotating programmers, designers, and founders through a day of answering emails directly to customers. The dividends of doing this were almost as high as having Jason run it all in the early years. We fixed an incredible number of minor niggles and annoying bugs because programmers found it easier to solve the problem than to apologize for why it was there.

It's not easy doing this! Customers often offer their valuable insights wrapped in rude language, unreasonable demands, and bad suggestions. That's why many founders quit the business of dealing with them at the first opportunity. That's why few companies ever do "Everyone On Support". That's why there's such eagerness to reduce support to an AI-only interaction.

But quitting dealing with customers early, not just in support but also in sales, is an incredible handicap for any startup. You don't have to do everything that every customer demands of you, but you should certainly listen to them. And you can't listen well if the sound is being muffled by early layers of indirection.

When to give up

David Heinemeier Hansson

Most of our cultural virtues, celebrated heroes, and catchy slogans align with the idea of "never give up". That's a good default! Most

Full

Most of our cultural virtues, celebrated heroes, and catchy slogans align with the idea of "never give up". That's a good default! Most people are inclined to give up too easily, as soon as the going gets hard. But it's also worth remembering that sometimes you really should fold, admit defeat, and accept that your plan didn't work out.

But how to distinguish between a bad plan and insufficient effort? It's not easy. Plenty of plans look foolish at first glance, especially to people without skin in the game. That's the essence of a disruptive startup: The idea ought to look a bit daft at first glance or it probably doesn't carry the counter-intuitive kernel needed to really pop.

Yet it's also obviously true that not every daft idea holds the potential to be a disruptive startup. That's why even the best venture capital investors in the world are wrong far more than they're right. Not because they aren't smart, but because nobody is smart enough to predict (the disruption of) the future consistently. The best they can do is make long bets, and then hope enough of them pay off to fund the ones that don't.

So far, so logical, so conventional. A million words have been written by a million VCs about how their shrewd eyes let them see those hidden disruptive kernels before anyone else could. Good for them.

What I'm more interested in knowing more about is how and when you pivot from a promising bet to folding your hand. When do you accept that no amount of additional effort is going to get that turkey to soar?

I'm asking because I don't have any great heuristics here, and I'd really like to know! Because the ability to fold your hand, and live to play your remaining chips another day, isn't just about startups. It's also about individual projects. It's about work methods. Hell, it's even about politics and societies at large.

I'll give you just one small example. In 2017, Rails 5.1 shipped with new tooling for doing end-to-end system tests, using a headless browser to validate the functionality, as a user would in their own browser. Since then, we've spent an enormous amount of time and effort trying to make this approach work. Far too much time, if you ask me now.

This year, we finished our decision to fold, and to give up on using these types of system tests on the scale we had previously thought made sense. In fact, just last week, we deleted 5,000 lines of code from the Basecamp code base by dropping literally all the system tests that we had carried so diligently for all these years.

I really like this example, because it draws parallels to investing and entrepreneurship so well. The problem with our approach to system tests wasn't that it didn't work at all. If that had been the case, bailing on the approach would have been a no brainer long ago. The trouble was that it sorta-kinda did work! Some of the time. With great effort. But ultimately wasn't worth the squeeze.

I've seen this trap snap on startups time and again. The idea finds some traction. Enough for the founders to muddle through for years and years. Stuck with an idea that sorta-kinda does work, but not well enough to be worth a decade of their life. That's a tragic trap.

The only antidote I've found to this on the development side is time boxing. Programmers are just as liable as anyone to believe a flawed design can work if given just a bit more time. And then a bit more. And then just double of what we've already spent. The time box provides a hard stop. In Shape Up, it's six weeks. Do or die. Ship or don't. That works.

But what's the right amount of time to give a startup or a methodology or a societal policy? There's obviously no universal answer, but I'd argue that whatever the answer, it's "less than you think, less than you want".

Having the grit to stick with the effort when the going gets hard is a key trait of successful people. But having the humility to give up on good bets turned bad might be just as important.

Europe must become dangerous again

David Heinemeier Hansson

Trump is doing Europe a favor by revealing the true cost of its impotency. Because, in many ways, he has the manners

Full

Trump is doing Europe a favor by revealing the true cost of its impotency. Because, in many ways, he has the manners and the honesty of a child. A kid will just blurt out in the supermarket "why is that lady so fat, mommy?". That's not a polite thing to ask within earshot of said lady, but it might well be a fair question and a true observation! Trump is just as blunt when he essentially asks: "Why is Europe so weak?".

Because Europe is weak, spiritually and militarily, in the face of Russia. It's that inherent weakness that's breeding the delusion that Russia is at once both on its last legs, about to lose the war against Ukraine any second now, and also the all-potent superpower that could take over all of Europe, if we don't start World Word III to counter it. This is not a coherent position.

If you want peace, you must be strong.

The big cats in the international jungle don't stick to a rules-based order purely out of higher principles, but out of self-preservation. And they can smell weakness like a tiger smells blood. This goes for Europe too. All too happy to lecture weaker countries they do not fear on high-minded ideals of democracy and free speech, while standing aghast and weeping powerlessly when someone stronger returns the favor.

The big cats in the international jungle don't stick to a rules-based order purely out of higher principles, but out of self-preservation. And they can smell weakness like a tiger smells blood. This goes for Europe too. All too happy to lecture weaker countries they do not fear on high-minded ideals of democracy and free speech, while standing aghast and weeping powerlessly when someone stronger returns the favor.

I'm not saying that this is right, in some abstract moral sense. I like the idea of a rules-based order. I like the idea of territorial sovereignty. I even like the idea that the normal exchanges between countries isn't as blunt and honest as those of a child in the supermarket. But what I like and "what is" need separating.

Europe simply can't have it both ways. Be weak militarily, utterly dependent on an American security guarantee, and also expect a seat at the big-cat table. These positions are incompatible. You either get your peace dividend -- and the freedom to squander it on net-zero nonsense -- or you get to have a say in how the world around you is organized.

Which brings us back to Trump doing Europe a favor. For all his bluster and bullying, America is still a benign force in its relation to Europe. We're being punked by someone from our own alliance. That's a cheap way of learning the lesson that weakness, impotence, and peace-dividend thinking is a short-term strategy. Russia could teach Europe a far more costly lesson. So too China.

All that to say is that Europe must heed the rude awakening from our cowboy friends across the Atlantic. They may be crude, they may be curt, but by golly, they do have a point.

Get jacked, Europe, and you'll no longer get punked. Stay feeble, Europe, and the indignities won't stop with being snubbed in Saudi Arabia.

Europe's impotent rage

David Heinemeier Hansson

Europe has become a third-rate power economically, politically, and militarily, and the price for this slowly building predicament is now due all at

Full

Europe has become a third-rate power economically, politically, and militarily, and the price for this slowly building predicament is now due all at once.

First, America is seeking to negotiate peace in Ukraine directly with Russia, without even inviting Europe to the table. Decades of underfunding the European military has lead us here. The never-ending ridicule of America, for spending the supposedly "absurd sum" of 3.4% of its GDP to maintain its might, coming home to roost.

Second, mass immigration in Europe has become the central political theme driving the surge of right-wing parties in countries across the continent. Decades of blind adherence to a naive multi-cultural ideology has produced an abject failure to assimilate culturally-incompatible migrants. Rather than respond to this growing public discontent, mainstream parties all over Europe run the same playbook of calling anyone with legitimate concerns "racist", and attempting to disparage or even ban political parties advancing these topics.

Third, the decline of entrepreneurship in Europe has lead to a death of new major companies, and an accelerated brain drain to America. The European economy lost parity with the American after 2008, and now the net-zero nonsense has lead Europe's old manufacturing powerhouse, Germany, to commit financial harakiri. Shutting its nuclear power plants, over-investing in solar and wind, and rendering its prized car industry noncompetitive on the global market. The latter leading European bureaucrats in the unenviable position of having to both denounce Trump on his proposed tariffs while imposing their own on the Chinese.

A single failure in any of these three crucial realms would have been painful to deal with. But failure in all three at the same time is a disaster, and it's one of Europe's own making. Worse still is that Europeans at large still appear to be stuck in the early stages of grief. Somewhere between "anger" and "bargaining". Leaving us with "depression" before we arrive at "acceptance".

Except this isn't destiny. Europe is not doomed to impotent outrage or repressive anger. Europe has the people, the talent, and the capital to choose a different path. What it currently lacks is the will.

I'm a Dane. Therefore, I'm a European. I don't summarize the sad state of Europe out of spite or ill will or from a lack of standing. I don't want Europe to become American. But I want Europe to be strong, confident, and successful. Right now it's anything but.

The best time for Europe to make a change was twenty years ago. The next best time is right now. Forza Europe! Viva Europe!

Leave it to the Germans

David Heinemeier Hansson

Just a day after JD Vance's remarkable speech in Munich, 60 Minutes validates his worst accusations in a chilling segment on

Full

Just a day after JD Vance's remarkable speech in Munich, 60 Minutes validates his worst accusations in a chilling segment on the totalitarian German crackdown on free speech. You couldn't have scripted this development for more irony or drama!

This isn't 60 Minutes finding a smoking gun in some secret government archive, detailing a plot to prosecute free speech under some fishy pretext. No, this is German prosecutors telling an American journalist in an open interview that insulting people online is a crime and retweeting a "lie" will get you in trouble with the law. No hidden cameras! All out in the open!

Nor is this just some rogue prosecutorial theory. 60 Minutes goes along for the ride with German police, as they conduct a raid at dawn with six armed officers to confiscate the laptop and a phone of a German citizen suspected of posting a racist cartoon. Even typing out this description of what happens sounds like insane hyperbole, but you can just watch the clip for yourself.

And this morning raid was just one of fifty that day. Fifty raids in a day! For wrong speech, spicy memes, online insults of politicians, and other utterances by German citizens critical of their government or policies! Is this is the kind of hallowed democracy that Germans are supposed to defend against the supposed threat of AfD?

As I noted yesterday, even Denmark has some draconian laws on the books limiting free speech. And they've been used in anger too. Although I've yet to see the kind of grotesque enforcement -- six armed officers at dawn coming to confiscate a laptop! -- but the trend is none the less worrying all across Europe, not just in Germany.

I suppose this is why European leaders are in such shock over Vance's wagging finger. Because they know he's dead on, but they're not used to getting called out like this. On the world stage, while they just had to sit there. I can see how that's humiliating.

But the humiliation of the European people is infinitely greater as they're gaslit about their right to free speech. That Vance doesn't know what he's talking about. Oh, and what about the Gulf of America?? It's pathetic.

So too is the apparent deep support from many parts of Europe for this totalitarian insanity. I keep hearing from Europeans who with a straight face will claim that of course they have free speech, but that doesn't mean you can insult people, hurt their feelings, or post statistics that might cast certain groups in a bad light.

Madness.

Madness.

"The party told you to reject the evidence of your eyes and ears. It was their final, most essential command."

-- Orwell, 1949

Europeans don't have or understand free speech

David Heinemeier Hansson

The new American vice president JD Vance just gave a remarkable talk at the Munich Security Conference on free speech and mass

Full

The new American vice president JD Vance just gave a remarkable talk at the Munich Security Conference on free speech and mass immigration. It did not go over well with many European politicians, some of which immediately proved Vance's point, and labeled the speech "not acceptable". All because Vance dared poke at two of the holiest taboos in European politics.

Let's start with his points on free speech, because they're the foundation for understanding how Europe got into such a mess on mass immigration. See, Europeans by and large simply do not understand "free speech" as a concept the way Americans do. There is no first amendment-style guarantee in Europe, yet the European mind desperately wants to believe it has the same kind of free speech as the US, despite endless evidence to the contrary.

It's quite like how every dictator around the world pretends to believe in democracy. Sure, they may repress the opposition and rig their elections, but they still crave the imprimatur of the concept. So too "free speech" and the Europeans.

Vance illustrated his point with several examples from the UK. A country that pursues thousands of yearly wrong-speech cases, threatens foreigners with repercussions should they dare say too much online, and has no qualms about handing down draconian sentences for online utterances. It's completely totalitarian and completely nuts.

Germany is not much better. It's illegal to insult elected officials, and if you say the wrong thing, or post the wrong meme, you may well find yourself the subject of a raid at dawn. Just crazy stuff.

I'd love to say that Denmark is different, but sadly it is not. You can be put in prison for up to two years for mocking or degrading someone on the basis on their race. It recently become illegal to burn the Quran (which sadly only serves to legitimize crazy Muslims killing or stabbing those who do). And you may face up to three years in prison for posting online in a way that can be construed as morally supporting terrorism.

But despite all of these examples and laws, I'm constantly arguing with Europeans who cling to the idea that they do have free speech like Americans. Many of them mistakenly think that "hate speech" is illegal in the US, for example. It is not.

America really takes the first amendment quite seriously. Even when it comes to hate speech. Famously, the Jewish lawyers of the (now unrecognizable) ACLU defended the right of literal, actual Nazis to march for their hateful ideology in the streets of Skokie, Illinois in 1979 and won.

Another common misconception is that "misinformation" is illegal over there too. It also is not. That's why the Twitter Files proved to be so scandalous. Because it showed the US government under Biden laundering an illegal censorship regime -- in grave violation of the first amendment -- through private parties, like the social media networks.

In America, your speech is free to be wrong, free to be hateful, free to insult religions and celebrities alike. All because the founding fathers correctly saw that asserting the power to determine otherwise leads to a totalitarian darkness.